The Old Copper Culture |

North America's First Metal Miners |

Have you ever thought about who the first metal miners and metal workers in North America were? What metal did they mine, where did they mine it, and what did they do with the metal? In order to find the answers to these intriguing questions we have to look back several thousand years before the birth of Christ. Large deposits of 99%+ pure native copper are known on the North Shore of Lake Superior, Isle Royale and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan. Reports of these copper deposits were heard by the earliest French explorers of the Great Lakes Region, beginning in 1608 with Champlain. He received a foot long specimen of native copper from an Algonquin Indian chief and sent it to King Henry IV of France. There were no immediate attempts to locate the source of this copper. However, prior to 1800 there were attempts to locate the source of the native copper that was spoken of by the indians of the region. These early attempts to locate and exploit the copper deposits ended in failure. By the mid 1840s, when the first modern copper mines were opened in the Keweenaw Peninsula, miners began to find traces of earlier mining efforts. Throughout the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale, pits and trenches dug into the rock were discovered, some as deep as 20 feet and others only a few feet deep. These pits and trenches showed evidence of copper having been removed from surrounding rock, and in some cases copper was found partially worked out of the rock but still in place. In association with these pits and trenches were found tons of grooved and ungrooved stone hammers, as well as some copper artifacts (knives, spearpoints, spuds, awls, etc.). An interesting point of fact is that these old copper workings were found on every copper lode discovered on the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale by miners in historic times. It was the presence of these old copper workings which led to the discovery of many of the copper deposits that were mined in historic times. Many theories have been advanced as to who these early copper miners were, some both incredible and ludicrous. These theories run the gamut from Phoenicians to Berbers, Bronze Age Europeans to Vikings, but there is no real archeological evidence to support these theories. Our own Euro-centrist racial bigotry allows many to ignore the obvious, that being that this copper was first discovered, mined and fashioned into tools, weapons and ornaments by the indigenous peoples of the region. Rather than admit that indigenous peoples could have mined native copper and fashioned items for everyday use, some "scholars" would have us believe that the copper was mined and worked by a "virtually unknown race of people" or Euro-Mediterranean peoples. There is, in fact, unbroken continuity in indigenous peoples, based upon artifact and skeletal evidence, in the Upper Great Lakes Region. Prehistoric Native Americans began to populate the area we today call Wisconsin at least 11,500 years ago. The end of the last Ice Age, the Pleistocene Epoch, saw the first human inhabitants arrive in the Western Great Lakes Region. As the glaciers receded vast new terrritories were opened for habitation. These post-Ice Age hunter-gatherer cultures have been named the Archaic Period or Tradition. In the Great Lakes Region the Archaic Period spanned from about 6500-1000 BC or 8500-3000BP (Before Present). One of the lasting effects of the last glacial period on the Great Lakes Region was the scouring of the rock that holds the copper deposits. This glacial scouring action exposed veins of native copper, as well as shearing off copper pieces of varying sizes, transporting them miles, or even hundreds of miles to the south. This transported copper, found mostly in glacial gravel deposits, is known as "float copper". It was deposited as the glaciers melted and receded northward. This float copper is found in sizes from that of less than a pea to many tons in weight. Float copper was readily available to the indigenous population during the Archaic Period. Experimentation would have demonstrated that this copper was malleable and could be fashioned into useful shapes. It is only a small step from finding the float copper to finding the exposed copper veins. The first indigenous peoples who actually mined and utilized the copper have been labeled "Old Copper Complex" or "Old Copper Culture" by archeologists. There is disagreement among the archeological community as to the time period to ascribe to the Old Copper Complex. Dates range from over 7000 years BP to 3000 years BP. The greatest disagreement seems to be over the beginning age of the Old Copper Complex. Carbon-14 testing of organic materials found with Old Copper Complex artifacts has established a date of at least 6000 years BP. Carbon testing of wood remains found in sockets of artifacts in our own collection has produced dates of 5700+ years BP. Copper was still being used up to proto-historic times, long after the decline of the Old Copper Complex. The copper artifacts from the Old Copper Complex differ from those of later manufacture. Since I earlier stated that there is no physical evidence of the Lake Superior copper deposits having been worked by those other than indigenous peoples, what evidence exists to prove that these indigenous peoples were the ones who worked the copper deposits and manufactured the copper artifacts found today? |

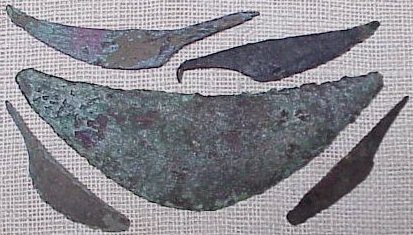

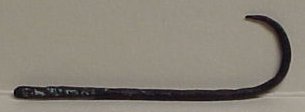

The first hard evidence came, in May of 1945, when two fishermen found some artifacts projecting from the eroding bank of the Mississippi River at an old steamboat landing site known as Osceola Landing, in Grant County, Wisconsin. Following this initial discovery, numerous copper artifacts were removed from the site by local collectors and were subsequently identifed as Old Copper Complex artifacts. Old Copper Complex artifacts include, but are not limited to, socketed spuds (photo 1), Crescents (photos 2,3,4 & 5), Fishhooks and harpoons (photo 8), conical spear and atlatl dart points (photo 6), awls, rat-tail spearpoints (photo 7), knives (photos 3,4,8,9 & 10), socketed spearpoints (photos 8,11 & 12), and other pieces of undetermined usage, as well as beads and bracelets, none of which had previously been found in situ prior to those at the Osceola Site, all previous finds being surface finds or isolated caches. Of great importance was the discovery, by archeologists, of skeletal remains in association with many copper and chipped stone artifacts. It is estimated that there were approximately 500 burials at the Osceola Site. The major contribution of the Osceola Site was the demonstration of a cultural complex that included Old Copper Culture artifacts. The Osceola Site tied Old Copper Culture Complex artifacts to a distinctive chipped stone industry and burial complex. |

Photo 1 - 4" socketed spud |

Photo 2 - two crescents, one spiral and 4 rolled beads (top) |

Photo 3 - three crescent and one tanged knife. (second from bottom) |

Photo 4 - four tanged knives and 8" crescent |

Photo 5 - crescent (center left), celts, and bracelet (top left) |

Photo 6 - conical points (top row), fishhooks and three harpoons (barbed pieces) |

Photo 7- Rat-tail spearpoints, 3rd from left has a native silver tang, center point is 3/4 native silver |

Photo 8 - 15" gaffhook, knife and spearpoint |

Photo 9 - Knives and spearpoint (vertical - bottom) |

Photo 10 - knife/scraper and rings |

Photo 11 - Variety of spearpoint types |

Photo 12 - variety of spearpoint types |

It was not until June of 1952 that another Old Copper Complex site was discovered, this occurred on the western edge of Oconto, in Oconto County, Wisconsin, near the Oconto River.. Thirteen year old Donald Baldwin was playing in an abandoned gravel pit when he found human skeletal remains. Initial investigation by the Oconto County Historical Society revealed numerous burials accompanied by copper artifacts. The site was soon more extensively examined by staff from the Wisconsin Historical Society and Milwaukee Public Museum. It was found that a major portion of the original burial site had been removed by commercial gravel operations in the 1920s but 45 burials were identified as remaining. Associated with these burials were Old Copper Complex artifacts in the form of 7 awls, 4 crescents, 3 clasps, 1 socketed spearpoint, 1 fish-tail spearpoint, 1 ovoid spearpoint, 1 fishhook, 1 coiled copper bead, 1 bracelet, and 1 spatulated artifact. Awls were found to be the most frequently occurring artifact, just as they had been at the Osceola Site. In 1953, A Late Old Copper Complex site (approximately 3000BP) was discovered in Algoma Township, Winnebago County, Wisconsin, on the south shore of Lake Butte des Mortes, on the farm of Matt Reigh. The Reigh Site, like the Oconto Site, was uncovered in part by commercial gravel operations. Burials of 43 individuals were uncovered along with copper artifacts identified as Old Copper Complex. As with the Oconto Site, an unknown number of burials were destroyed by the gravel operation prior to the archeological investigation being undertaken. These three sites, with their skeletal remains, distinctive chipped-stone artifacts and Old Copper Complex copper artifacts, support the unbroken continuity of indigenous peoples in the Upper Great Lakes. Evidentiary finds at sites in Canada support the findings at the Wisconsin sites. Old Copper Complex artifacts have been found at sites in the Canadian Provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec.The Morrison Island-6 Site, located on an island in the Ottawa River, was found to contain 18 burials and 276 copper artifacts, including a spud, projectile points, knives, and others. Also of interest was the discovery of worked and unworked copper scraps, indicating copper implement and weapon manufacture on the site. A carbon-14 date places this site at 4700BP, clearly an Old Copper Complex Site. The Caribou Lake Site contained a cremation pit with skeletal fragments and tooth enamel remains, along with copper artifacts. Carbon-14 dating placed this site at 3900BP. While Old Copper Complex artifacts have been found from Alberta in the west to Quebec in the east in Canada, and as far west as North Dakota, as far east as New York and as far south as Kentucky in the United States, the center of the Old Copper Complex is generally agreed to be in Wisconsin. How did Old Copper Complex artifacts come to be scattered so far afield? The answer to this question is trade. The presence of specific types of stone and shell artifacts not indigenous to Wisconsin demonstrate that widespread trading took place. How did these Archaic Tradition peoples obtain and work the copper that identifies them as the Old Copper Complex? As mentioned earlier, the source of the copper was the north shore of Lake Superior, Isle Royale, and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, as well as glacial float deposits to the south left by the receding glaciers. How were these people able to extract the native copper from the hard igneous rock in which most of it is found? Quite simply, the answer is fire, water and stone. When a copper vein was discovered , fires were built on the rock and kept burning until the rock become quite hot, water was then thrown on the heated rock and the rapid cooling fractured it. This process was repeated numerous times before these ancient copper miners began using stone hammers to break the copper free from the now fractured rock. Stone hammers were also used to break off pieces of copper small enough to be worked. |

Diorama of Old Copper Complex Indians working a copper vein |

The stone hammers were of two varieties, grooved and ungrooved. Grooved hammers could have handles attached while the ungrooved hammers were merely held in one or both hands. Hammerstones have been found weighing from 1 to more than 30 pounds. Early modern-day miners removed literally tons of stone hammers from individual sites in the Keweenaw Peninsula and on Isle Royale in the 1800s. There have been incredible, but totally unsubstantiated, claims made as to the time and manpower required to create the ancient copper pits and as to the amount of copper mined. Beginning with Drier and Du Temple in 1961 and Mertz in 1967, through Sodders in 1990, figures of .5 to 1.5 billion pounds (yes billions, not millions) have been put forth. Sodders postulates "it is believed that as many as 10,000 miners, labored some 1,000 years, in an estimated 10,000 Copper Range pits". Drier and Du Temple get to their figures with the following assumptions in their 1961 work "Prehistoric Copper Mining in the Lake Superior Region": "If one assumes that an average pit is 20 feet in diameter and 30 feet deep, then it appears that something like 1000 to 1200 tons of ore were removed per pit. If the ore averaged 5% or 100 pounds per ton then approximately 100,000 pounds of copper were removed per pit. If 5000 pits existed, as earlier estimates indicated (and all are copper bearing), then 100,000 pounds per pit in 5000 pits means that 500,000,000 pounds of copper were mined in prehistoric times- all of it without anything more than fire, stone hammers and manpower. If the ore sampled 15% and if more than 5000 pits existed, then over 1.5 billion pounds of copper were mined". One has to ask the obvious question, where did all this mined copper go? Some scholars would have us believe that the vast majority was taken by Phoenicians, Berbers, Bronze Age Europeans or Vikings in a huge international copper trade centering in the Lake Superior Region. Where is the archeological evidence to support these theories? The truth is it does not exist. There are no identified community or camp sites, no burial remains, and no artifacts to support any of these theories. All of these things do exist to demonstrate that the indigenous peoples were, in fact, the ones who mined the copper and fashioned it into implements, weapons and ornaments Sodders figures of 10,000 miners laboring for 1000 years in an estimated 10,000 pits are pure unsubstantiated bunk. Who counted the 10,000 miners? The Copper Culture copper pits were actually worked much longer than 1000 years, proven by archeological evidence. As for the estimated 10,000 pits, who estimated that number and based upon what data. There has never in recorded history been a comprehensive study and tally done of the number pits, what is the evidence for this "estimated" number of copper pits. The estimates put forth by Drier and Du Temple are easily debunked. They start with the errroneous and unsupported assumption that the average pit was 20 feet in diameter and 30 feet deep. No study of these ancient copper pits has ever determined an average size and few, if any, pits have ever been reported as deep as 30 feet, when in fact many ancient pits or trenches barely scratched the surface by more than a few feet. The asumption of 5000 pits has no supporting documentation as a comprehesive study of the number of pits has never been undertaken and published. Their 5% to 15% copper content is flawed since content can run from zero to 100% (mass copper). The amount of copper in the country rock isn't constant or regular, an expensive fact learned by many early modern mining companies. All of the numbers offered up by Drier and Du Temple are based solely on conjecture with no basis in fact. So much for flights of fancy, let us now examine how the Old Copper Complex Indians produced their copper implements, weapons and ornaments. Unless copper is cast, and no evidence yet exists to demonstrate that the Old Copper Complex possessed the technology to cast copper, it must be cold hammered, which produces brittleness in the copper, or annealed (heated and then worked to prevent brittleness). Small stone hammers could be used to form basic shapes and then edges could be sharpened or shaped by being stone ground. If one closely examines a large number of Old Copper Complex artifacts it becomes apparent that two types of copper were utilized and that each required a different method of working to produce usable items. Either solid chunks of copper were used or thin sheet copper was used. The chunks of copper were first pounded into "preforms" which were basic shapes that could be used for more than one type of implement or weapon. These were followed by "blanks" which were the overall size and shape of the finished item but were not completed for use. Finally, there was the finshed artifact which had all the characteristics of a usable implement, weapon or ornament which might include such features as a sharpened edge, as in the case of a knife, scraper or spearpoint, a sharp point, as in the case of an awl, fishhook or spearpoint ,or a socket, as in the case of some types of knives, spearpoints and atlatl darts. The use of sheet copper requires that the copper be folded over and over while being pounded into the desired shape. We have artifacts in our collection in which as many as six distinct folds can be seen. These folds can be found in all types of copper artifacts - spearpoints, knives, awls, atlatl dart points, crescents, spuds, and others. This folding process would take the finished artifact through the same preform and blank manufacturing stages. We have self-collected hundreds of worked and scrap pieces of copper associated with artifact finds that point to the presence of numerous manufacturing sites. We also have found worked copper "bars" (for lack of a better term) which are up to 1 1/2" square and 8" long which were most likely used as trade items as they were easily transportable in that form. Given the primitive means of working the raw copper, the workmanship on many of these artifacts must be judged to be excellent. What I find interesting is the extent to which most archeologists appear to be unaware of the number of Old Copper Culture sites and artifacts that actually exist. It is the amateur archeologists, indian artifact collectors and metal detectorists who have a good idea of the extent of Old Copper Culture sites. My father and I are aware of many sites, as are other collectors, that are unknown to professional archeologists, and which have produced, and continue to produce a multitude of copper artifacts. |

Copper preform |

Copper knife blank |

Copper preform |

Copper preform |

Unfinished folded blank for a conical point |

Folded preform |

Folded preform |

Copper "bars" (second from bottom measures 1 1/2" x 1 1/2" x 8") They are not flat as they appear but rather squared |

While not professional archeologists, my father and I have been collecting Old Copper Complex artifacts for more than 30 years and between us have amassed a collection of over 2500 copper artifacts, about 2300 of which have been self-collected., as well as some stone and pottery artifacts (different period) collected from the same area as the Old Copper Complex sites. Our collection includes Old Copper Complex artifacts from Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, Illinois, Kentucky, Manitoba and Ontario. When hunting artifacts we log each find as to type, measurements, location and date found, and produce a sketch of each artifact. The majority of our finds come from river banks and shallow water, we do not despoil archeological sites with our collecting . We steadfastly refrain from excavating burials although we know of their locations, considering this action by other than a professional archeologist to be grave robbing. Unfortunately most professional archeologists look upon artifact collectors who use metal detectors with disdain, unworthy of serious recognition and seem to place them in the same category as "pot hunters". However, I would argue that the artifacts that we, and others, collect would otherwise remain buried and be unavailable for study. We have made our collection available for study and have been visited by archeologists for that purpose. Without artifact collectors like us the true extent of the Old Copper Complex would not be as well defined as it is. All artifacts pictured on this website are from the collection of Dr. E.W. Johnson and David Johnson. The collecting and study of Old Copper Complex artifacts is an interesting adjunct to my overall mining artifact collection. Click on "My Mining Artifact Website" below to see some of my mining artifact collection. To see additional Old Copper Complex artifacts click on the first button below. The third button below will take you to sources used for this website. Button four below will take you to my "Artifact Collecting" site showing where many of our artifacts were found. Button five below will take you to related websites. |

My Mining Artifact Website |

More Old Copper Complex Artifacts From Our Collection |

Sources for this website |

Artifact Collecting |

Email me at |

This page was last updated on: April 26, 2004

7" Tanged Spearpoint |

4 1/2" Socketed Spearpoint |

Other Side of Socketed Spearpoint |

7 1/2" & 5" Awls |

Preform with Native Silver (center) |

4 1/2" Tanged Spearpoint |

3" Conical Point |

3" Conical Point Showing Folds |

Click on the first button below to see more copper artifacts from our collection. |

Links to other Copper Culture Sites |

V |

I |

I |

Native Silver |

4 1/2" Crecent Knife |

5 1/2" Tool of Unknown Purpose |

3 1/2" Tanged Point |

3 3/4" Step Socketed Point |

5 1/2" Conical Socketed Point |

Please contact me if you have copper artifacts to sell |

7 1/2" copper chisel |

Closeup of two pin holes to secure point to wood shaft |

2 1/2" fishhook |

Unusual Point with 2 pinholes to secure to wood shaft |

Other side of above point |

. |